Abstract

The focus of this research study is on asynchronous online learners at a small, private university in the Midwestern United States. The data was compiled during the fall 2020 semester following the emergency online semester (in spring 2020) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study examines challenges and barriers to student success and attempts to draw conclusions on how institutions can support asynchronous online learners. The results were also compared to results gathered in spring 2020 to find similarities or changes as time progressed. Many resultant categories were similar, indicating that students had similar concerns and thoughts across the semesters, even after several months had passed of the pandemic situation. More positives were reported in the second semester, perhaps indicating an adaptation by the student to the new pandemic situation. These data are being shared as information that may be useful during the continuing pandemic (and post-pandemic) in consideration of student success in the asynchronous virtual classroom.

Background

Online learning in higher education has increased over time (Simonson et al., 2019), and as we look ahead to the post-COVID-19 pandemic environment, the online modality may rise even more. Studying student success factors and challenges in online learning may assist institutions to be better prepared to serve student needs. Student success in the higher education classroom is typically defined by the attainment of learning outcomes (Dean, 2015). In the online classroom, student success and achievement of these outcomes is dependent on several conditions, including the students’ general abilities, prior knowledge in the subject matter, and learning styles (Simonson et al., 2019). Even when these elements align, are there other factors that can affect student success in the online setting? If external challenges and barriers are present, how can institutions support students and help lead them toward these successful outcomes?

During the global pandemic of 2020-2021, students were presented with challenges to their environments that included time, stress, health, work, and family interruptions (Covelli, et al., 2020). These challenges, however, were not unique to the pandemic. Students of all ages are increasingly overscheduled – whether due to co-curricular activities, part-time or full-time work responsibilities, or family duties related to siblings, children, parental caregiving, or grandparent needs. Asynchronous online learning can assist these students by providing a learning environment that is conducive to balancing these challenges (Simonson et al., 2019).

Asynchronous online learning occurs when the instructor and the student are in different physical spaces and the activities of teaching and learning are happening at separate times (Brady & Pradhan, 2020). This type of learning requires students to use learning strategies that are often self-regulated, and the types of self-regulated strategies employed can lead to students’ satisfaction with the learning environment (Choi, 2016). In other words, in asynchronous online learning, student success is dependent on the student’s ability to be self-directed and to manage their time and self-motivation (Choi, 2016).

Asynchronous online learning provides educational opportunities for students with limited time or increased work demands (Brady & Pradhan, 2020). It offers flexibility (Alkan & Bumen, 2020) and provides a learning environment where students have time to think about their responses to various types of assessment including discussion forums (Simonson et al., 2019). Lin & Gao (2020) examined both asynchronous and synchronous courses taught during the emergency stage of the pandemic and found that advantages to asynchronous learning included self-control of learning and self-directed learning. Other terms used to describe the advantages of asynchronous learning were: more efficient, deeper learning, and using time wisely (Lin & Gao, 2020).

Alkan & Bumen (2020) indicated that advantages are greater than disadvantages in the asynchronous environment but must be accompanied by instructional and student factors in order to produce a successful learning environment. These factors included interaction within the asynchronous platform, student-centered learning, and feedback (Alkan & Bumen, 2020). Karkar-Esperat’s (2018) findings supported these factors and indicated the instructor should be active in the classroom and create an environment of continuous interaction between the instructor and the students. To achieve success in the asynchronous online classroom, students must also be engaged in learning (Waters, 2012). It is not a passive environment; therefore, students who struggle with time management may find themselves less successful in this modality (Simonson et al., 2019). Koehler et al. (2020) suggested that students navigated asynchronous discussions in different ways, and that participating can be challenging for some students. Simonson et al. (2019) concurred that students must login regularly to class, practice good time management, and keep pace with the course activities. Other challenges included a feeling of isolation from other students and the instructor (Karkar-Esperat, 2018; Lin & Gao, 2020).

Many research efforts seeking to improve the online learning environment have examined best practices (Alkan & Bumen, 2020; Koehler et al., 2020, Ringler et al., 2015). While identifying best practices for instructors and designers is important, what are the institutional services that might assist student success rates? Additional research on students’ challenges and barriers may help shed light on institutional or instructional strategies to assist in student success, particularly in an uncertain pandemic environment.

Purpose of the Study

The research study presented here compares students’ reactions and challenges in asynchronous online courses during and after the initial emergency stages of the pandemic. Covelli et al. (2020) studied student reactions in asynchronous online courses during the COVID-19 emergency semester in spring 2020. Students were registered for asynchronous online courses that had no modality interruption due to the pandemic; however, it was found that students still had barriers and challenges to their success in learning (Covelli et al., 2020). As a follow-up, students’ reactions and challenges were then measured in asynchronous courses after the emergency stage (fall 2020). Again, the students were registered for asynchronous online courses with no modality interruption.

The asynchronous modality of instruction continues to be an option for many courses, therefore it is important to review students’ experiences post-emergency to understand if barriers and challenges have changed since the increase in virtual interactions inside and outside of higher education.

Research Questions:

- How do the students’ challenges compare between the emergency virtual semester vs. a post-emergency semester?

- How can institutions support student success in asynchronous online learning environments?

- How do the students’ barriers to success compare between the emergency virtual semester vs. a post-emergency semester?

Methodology

Population and Sample

The study took place at a small, liberal arts institution in the Midwestern United States in the fall of 2020. The courses were chosen using a convenience sample drawn from five undergraduate and nine graduate asynchronous online courses being offered in the fall 2020 semester. The courses included disciplines in health and business. The instructors each had numerous years of experience teaching asynchronous online courses. During the semester, this institution also held classes in other modalities including modified face-to-face (with social distancing and masking), hybrid, synchronous online, and hyflex. Students may have taken courses across these modalities; however, only data from the asynchronous online courses were examined in this study.

Thus, the study sample consisted of the responses to three questions completed by traditional age college students, adult degree-completion students, and graduate students in business and health administration. Because data were anonymized, the total number of students who participated is unknown. However, there were 39 responses to the questions that asked about challenges, 39 responses to the question regarding barriers, and 28 responses to the question regarding institutional support.

Procedures & Implementation

The study examined secondary data from course evaluations. The institution was concerned that it met the needs of its students during this unprecedented crisis. There was a need for direct guidance from students regarding how they could best be supported by the university during the global pandemic of SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19). Faculty in the College of Business and Health Administration were asked if they would be willing to add three open-ended questions to the regularly administered course evaluations. With the permission of those interested faculty, three open-ended questions were added to these regularly administered end-of-semester course evaluations. Responses to those questions were compiled and anonymized, for both respondents and courses, by administration. The data were then provided to the researchers as an Excel spreadsheet.

The questions to the students were as follows:

- What was your biggest challenge this semester?

- Moving forward, how can the University support you during and following the COVID-19 crisis?

- Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, what barriers to your success did you encounter while taking this online course?

These qualitative data were coded using a grounded theory approach and constant comparison methodology. The grounded theory approach helps to extract and develop meaning from qualitative data (Charmaz, 2009; Chun, 2003; Straus & Glaser, 1967). It is a reiterative process by which independent researchers generate open codes that can then be grouped into thematic super codes which can then be further refined using constant comparison methods. Two experienced qualitative analysis coders worked on the analysis separately. They then met and discussed the analysis thoroughly. Case definitions of each of the themes were created, and once again compared to the coding. Concordance between the two coders was 92% and a Cohen’s kappa of 0.79 was calculated, which indicates high inter-rater reliability. The definitions of the supercodes are shown in Appendix 1.

In order to ensure face and internal validity, all authors reviewed the case definitions and found them reasonable. Please note that individual student responses could lead to multiple codes. For example, the first question about challenges yielded 39 student responses, from which 88 initial coding responses were created. Below is an example that is demonstrative:

| Quotation Finding motivation to go back to school. Right now people are less busy and I’m working remotely so I can’t say I didn’t have time but the energy of the world is different, I don’t want to go engage. | Initial Codes Motivation Time management Community Engagement Employment |

Covelli et al. (2020) analyzed the qualitative data using SPSS Text Analytics, using word counts and automated coding. In the current study, manual coding and constant comparison methods were used instead of the automated analytics. The decision to change methods was made for three reasons. First, the sample was smaller, so manual coding was manageable. Secondly, the current method was expected to yield greater depth and granularity in results. Finally, the expected results would yield more actionable items.

Results

As described in the methodology, the students’ responses (from the fall 2020 semester) to three questions were categorized into initial codes and then supercodes. The results are shown below for each question, showing the count of initial codes for each item. The supercodes are shown in the color header lines, with the initial codes that fell into that supercode grouped under the supercode header. The results from the applied methodology were:

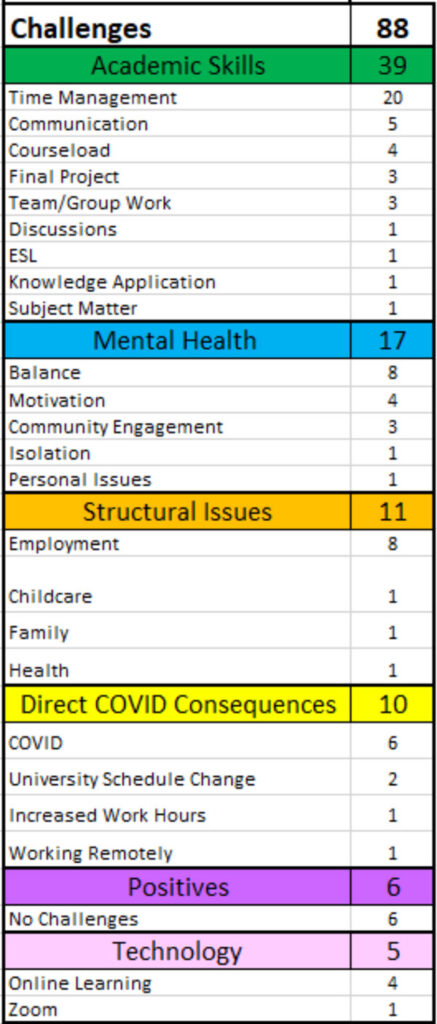

Table 1: Coded responses to “What was your biggest challenge this semester?” (from 39 student responses)

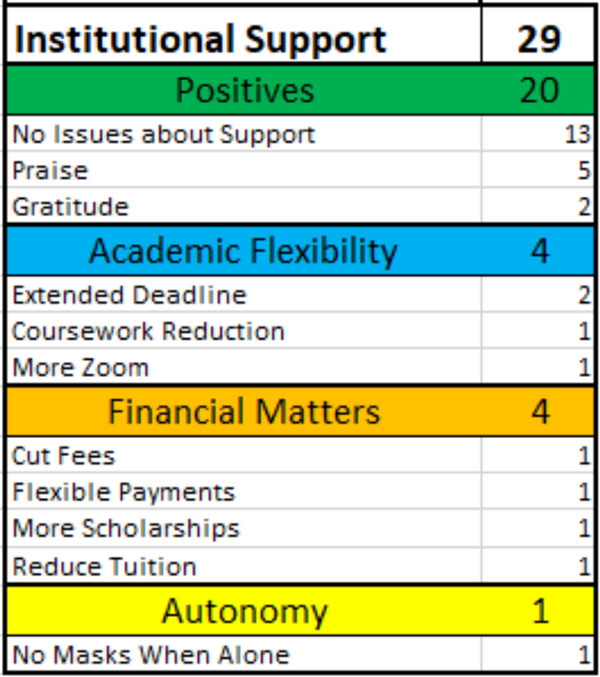

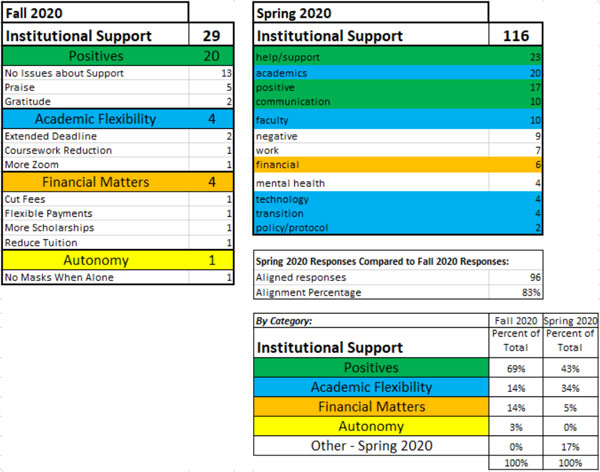

Table 2: Coded responses to “Moving forward, how can the University support you during and following the COVID-19 crisis?” (from 28 student responses)

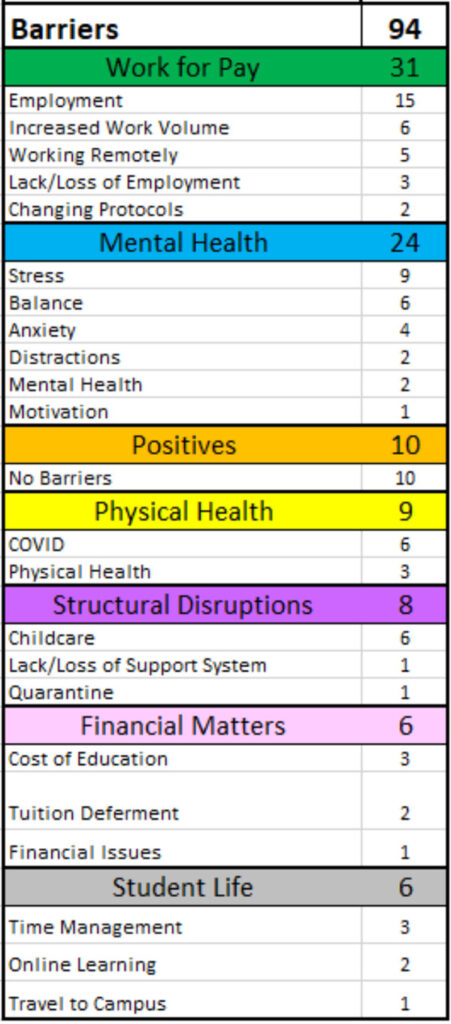

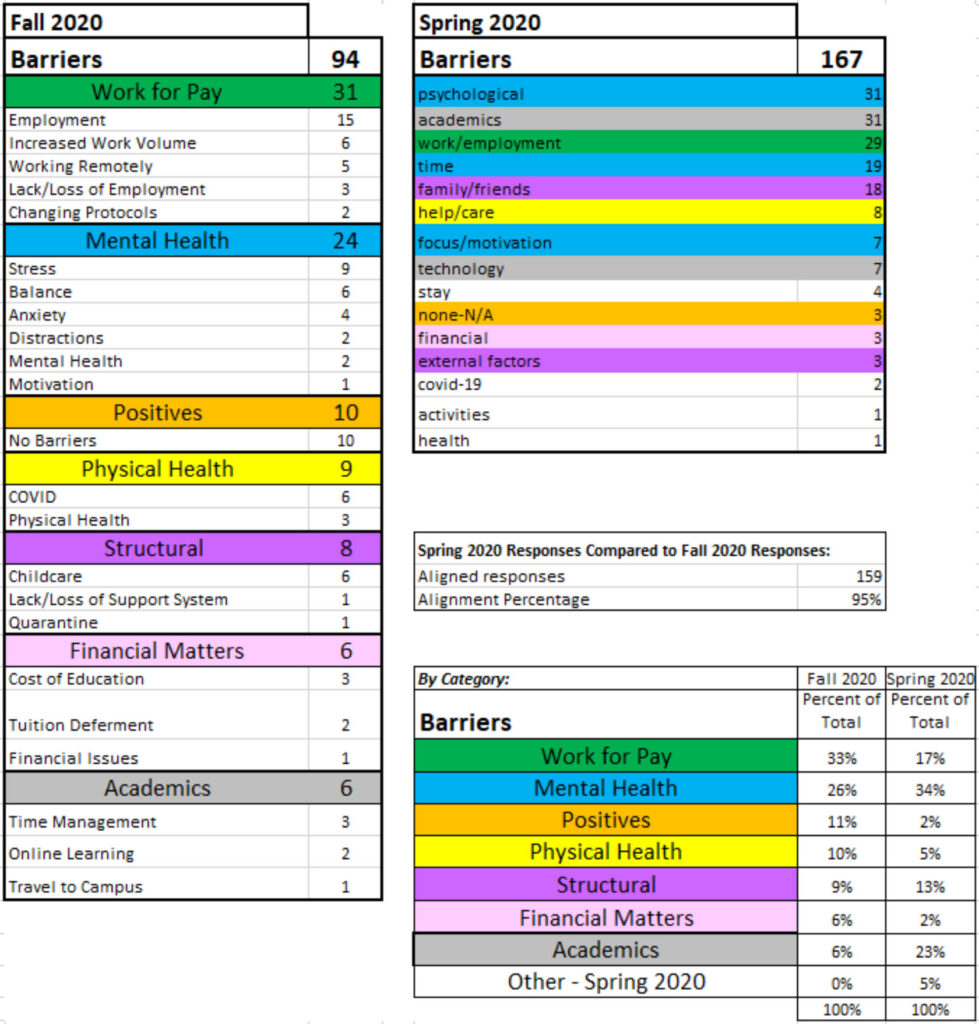

Table 3: Coded responses to “Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, what barriers to your success did you encounter while taking this online course?” (from 39 student responses)

These post-emergency semester fall 2020 results were then compared to the emergency semester spring 2020 results (Covelli et al., 2020) to see where alignment existed (or did not exist) across the semesters. It is noted that the methodologies of coding the responses varied across the two semesters: in spring 2020, IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Text Analysis software was utilized, while in fall 2020, the grounded theory approach was used (as described in methodology). When capturing the data from the Covelli et al. (2020) paper, any responses where the true meaning or context could not be identified (from the SPSS results) were removed prior to the comparison to the fall 2020 data (see Appendix 2).

Research Question #1: How do the students’ challenges compare between the emergency virtual semester vs. a post-emergency semester?

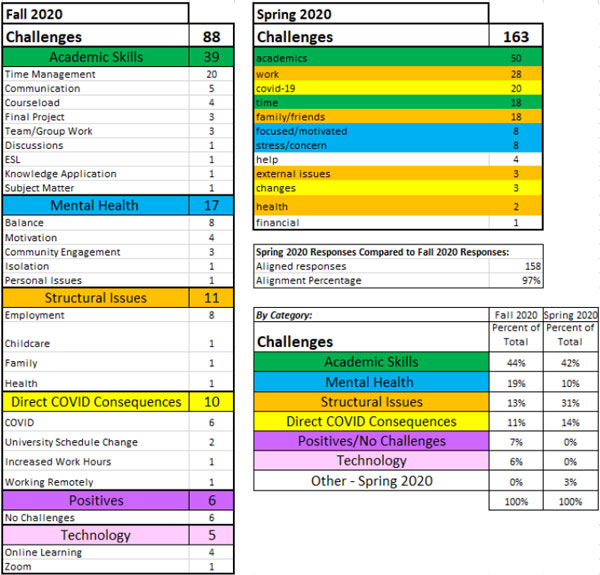

Table 4: Comparison of emergency and post-emergency semester data for Challenges

For “challenges” that students faced, “academics” was the largest category in both the spring and fall semester. The highest four categories represented 88% in the fall, and 97% in the spring. The overall alignment of categories between the semesters was very high (97%).

It is interesting that “help” and “financial” came up in the spring responses but not the fall.

Research Question #2: How can institutions support student success in asynchronous online learning environments?

Table 5: Comparison of emergency and post-emergency semester data for Institutional Support

For student comments on how the institution could support them, the largest category in both the spring and fall semester was related to positive themes. The highest three categories represented 97% in the fall, and 83% in the spring. The overall alignment of categories between the semesters was high (83%).

It is interesting that “work” and “mental health” came up in the spring responses but not the fall.

Research Question #3: How do the students’ barriers to success compare between the emergency virtual semester vs. a post-emergency semester?

Table 6: Comparison of emergency and post-emergency semester data for Barriers

For “barriers” that students faced, “work” was the largest category in the fall semester and a significant third-highest in the spring semester. “Mental health” was second highest in the fall and the highest in the spring. These two categories alone represented 59% in the fall, and 51% in the spring. The overall alignment of categories between the semesters was very high (95%).

Academics was a large category in the spring semester but was not as prevalent in the fall semester.

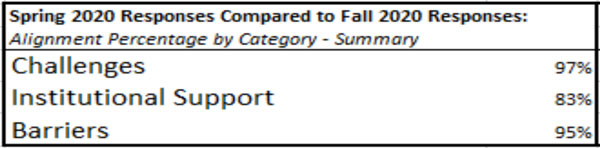

In summary, the semesters yielded very similar categorical results:

Table 7: Overall response category alignment summary

Discussion

Comparing the data from the first emergency asynchronous online class research study (spring 2020) and the post-emergency online class research study (fall 2020) finds very little has changed between the data collected on the two semesters. Similar to spring 2020, data from fall 2020 showed academics, mental health, and work were the biggest challenges and barriers students faced. Also interesting to note, financial and healthcare concerns remained surprisingly low, even as the pandemic continued to impact students into the fall semester.

Under the challenge category, mental health increased from 10% in spring 2020 to 19% in fall 2020. The results for structural issues under the challenge category did show improvement from 31% in spring down to 13% for fall. This could be the result of a combination of the institutional support and the student adapting better to the ever-changing situation. Financial matters did not come up in the fall semester; perhaps the students’ employment situation improved or government assistance eased the financial burden.

The student comment below articulates the ever-changing academic demands students faced as the pandemic continued into the fall semester. One of the comments to the student question: “What was your biggest challenge this semester?” is shown here:

“COVID, having been working remotely from home in isolation, made it more difficult to try to absorb material. Especially after sitting in front of a computer and Zoom calls. In the past, I always enjoyed coming home from work and spending some time on new material that was not work related. With working from home, by the time I was ready to start studying, I was spent. Had it not been for COVID, this would have been a class that I could pull myself into.”

As Choi (2016) mentioned, student success in asynchronous online learning depends on the ability to be self-directed, to be stewards of time management, and to be self-motivated. The challenges presented by the pandemic, as evidenced by the data above and the student comments, appear to present added barriers to these success factors.

Under the category of institutional support, the “positives” section saw an increase from 43% in spring 2020 to 69% in fall 2020. We could look to many issues for this positive increase, from faculty training and the ongoing support offered to both faculty and students. This might also include learning factors by instructors and students alike as individuals adjusted to the new normal patterns of virtual work, virtual learning, and other pandemic related activities.

While the institution generally received very good support scores in both spring and fall 2020 semesters, the comment below reflects the pressure the pandemic placed on students’ time management.

One of the comments regarding the question of institutional support “Moving forward, how can the university support you during and following the COVID -19 crisis?” is shown here:

“Just for faculty to be understanding and grant a little flexibility if, as an adult student, we need a little extra time to complete a project because of life happening around us.”

Under the barriers category, the “work for pay” section saw an increase from 17% in spring 2020 to 33% in fall 2020. As the pandemic moved into the fall semester, students saw an ever-increasing demand on workplace pressures which may have impacted their engagement in the academic space. Waters (2012) described the importance of student engagement in the asynchronous online classroom. If barriers to engagement existed, this may impact student success.

One of the comments on the barriers to success question “Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, what barriers to your success did you encounter while taking this online course?” is shown here:

“Extra work at my workplace. At the start of the pandemic, we had reduced hours but during the fall season, everything reopened, and work became busier and more demanding. I was having second thoughts on going to school, and when I did, I couldn’t qualify for any financial aid, only loans. No regrets so far. Just time management and lots of sacrifice.”

Pandemic fatigue, which is not a symptom of COVID, but rather referring to the ongoing stress from the pandemic’s impact on society, is currently being studied by healthcare professionals to help understand, diagnose, and treat the less visible effects on mental health. Educational professionals, such as Lin & Gao (2020), are also examining the pandemic’s impact on education to find insight as to what practices are working well. The goal of these two semester research projects was to try to identify, compare and contrast the impact on students taking asynchronous online classes as they adapted to the quickly evolving demands on academics, family, and work.

Conclusions and Implications to Practice

This study provides preliminary longitudinal data describing the evolution of student perspectives from the COVID-induced emergency online semester in spring 2020 and the fall 2020 semester.

The first implication is the academic community must be aware and sensitive to the evolving student experiences and attitudes. The survey shows that the student experience changed in several important dimensions such as increased demands in their workplace as well as exhaustion due to working from home, causing a reduction in a student’s ability to focus on their online learning. The issue of workplace demands and work-from-home has implications for teaching faculty. While faculty should not reduce academic performance standards, it is still important for faculty to be cognizant that students feel new/increased stress and pressure from their life “outside” the classroom (even the online “classroom”). The fact that student attitudes and experiences are evolving is another important implication. The academic community should be aware of and sensitive to these changes – students are not living in the same world as they did pre-pandemic. Indeed, it is likely the student experience will continue to evolve. The adage that “you never step in the same river twice” would seem to be a good admonition for faculty and administrators. It seems likely that a particular student is living a very different experience in each semester as their environment continues to change. It is important to avoid the temptation to assume that the student experience is “back to normal” or that this semester’s experience is the “new normal.” Again, student experiences will likely continue to evolve and, so too should the academic experience provided.

Clearly, the small sample size of this study limits the strength of any findings. Additionally, the population of asynchronous learners surveyed was diverse, including traditional undergraduate students, adult degree-completion, and adult graduate students. The demographics of the population was not tracked and may have provided insight into students’ success in the classroom. The sample size did not allow for reliable analysis of distinct groups.

The implications for future research are straightforward: collect similar data in future semesters to track the evolving student experience. This might include studies examining more specific aspects of time management, student engagement, motivation, work/life/academic balance, or connectedness. As the research suggests, there are numerous factors to a successful asynchronous online experience, and further study into these practices may assist instructors and institutions to provide the best possible academic experience. A more complex future study might also collect data on student, faculty, and administrative opinions of these various tactics, modifications, and accommodations implemented as institutions strive to respond to evolving student experiences.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Case definitions of supercodes

| CHALLENGES | What was your biggest challenge this semester? |

| Academics | Statements referring to student difficulties in meeting the requirements for their courses or at the university overall. |

| Mental Health | Statements referring to psychological, social, or emotional well-being. |

| Structural Issues | Statements referring to over-arching life issues, outside of the academic situation. |

| Direct Covid Consequences | Statements referring to situations which arose as a direct consequence of Covid. |

| Positives | Statements referring to the absence of challenges. |

| Technology | Statements referring to the use of new technologies or technological challenges. |

| INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT | Moving forward, how can the University support you during and following the COVID-19 crisis? |

| Positives | Statements of praise, gratitude, and compliments towards the university. |

| Academic Flexibility | Statements referring to changes towards course requirements or delivery. |

| Financial Matters | Statements referring to the students’ obligations of payments to the university. |

| Autonomy | Statements referring to the students’ rights or conditions of self-government |

| BARRIERS | Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, what barriers to your success did you encounter while taking this online course? |

| Work for Pay | Statements referring to employment or changes in employment. |

| Mental Health | Statements referring to psychological, social, or emotional well-being. |

| Positives | Statements of praise, gratitude, and compliments towards the university. |

| Physical Health | Statements referring to corporeal or somatic well-being. |

| Structural | Statements referring to lifestyle disruptions, separate from university life. |

| Financial Matters | Statements referring to economic consequences, both in terms of tuition and employment. |

| Academics | Statements referring to difficulties with new technology and issues of time management to meet course requirements. |

Appendix 2: Results removed from SPSS results from “Student reactions in asynchronous online learning in the COVID-19 emergency crisis in higher education” (Covelli et al. 2020)

| Question | SPSS Result Removed (Meaning or Context Unclear) |

| Biggest Challenge | biggest challenge, negative, positive |

| Institutional University Support | university, students, unsure, covid-19, reduced, staff, leader, events, communities, feelings, imbalance, focus |

| Barriers | negative, challenge, positive |

References

- Alkan, H., & Bümen, N. T. (2020). An action research on developing English speaking skills through asynchronous online learning. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 12(2), 127–148.

- Brady, A. K. & Pradhan, D. (2020, April 10). Learning without borders: Asynchronous and distance learning in the age of COVID-19 and beyond. ATS Scholar 1(3).

- Charmaz, K. (2009, May 24). Grounded theory. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. SAGE Publications.

- Choi, B. (2016). How people learn in an asynchronous online learning environment: The relationships between graduate students’ learning strategies and learning satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 42(1).

- Chun T., Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312118822927. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

- Covelli, B., Lindee, C., Valle, M., Vaughan, R., Behling, R., Griego, O. (2020, Fall). Student reactions in asynchronous online learning in the COVID-19 emergency crisis in higher education. The ACBSP Transnational Journal of Business, 20-24. https://cdn.ymaws.com/acbsp.org/resource/resmgr/tjb/TJB-Special_Issue-Reflection.pdf

- Dean, K. L. (2015). Understanding student success by measuring co-curricular learning. In L. C. Kennedy-Phillips, A. Baldasare, M. Christakis (Eds.), Measuring Cocurricular Learning: The Role of the IR Office, New Directions for Institutional Research (pp. 27+). Wiley.

- Karkar-Esperat, T. M. (2018). International graduate students’ challenges and learning experiences in online classes. Journal of International Students, 8(4), 1722–1735.

- Koehler, A. A., Fiock, H., Janakiraman, S., Cheng, Z., & Wang, H. (2020). Asynchronous online discussions during case-based learning: A problem-solving process. Online Learning, 24(4), 64–92.

- Lin, X., & Gao, L. (2020). Students’ sense of community and perspectives of taking synchronous and asynchronous online courses. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 169–179.

- Ringler, I., Schubert, C., Deem, J., Flores, J., Friestad-Tate, J., & Lockwood, R. (2015). Improving the asynchronous online learning environment using discussion boards. Journal of Educational Technology, 12(1), 15–27.

- Simonson, M, Zvacek, S., & Smaldino, S. (2019). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (7th ed.). North Carolina: Information Age Publishing.

- Strauss, A., & Glaser, B.G. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory.

- Waters, J. (2012). Thought-leaders in asynchronous online learning environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(1), 19–34.