Abstract

There is an abundance of research found in the literature regarding student career preparation that focuses on the increasing emphasis on soft skills by future employers (Dabke, 2015; Petrone, 2018; Majid et.al., 2019). A study by Jones et al., 2019, found that soft skills account for 85% of career success. The intention of this study was to measure the faculty perception as to which class activities are perceived most effective in heightening soft skill development, student learning, interest/engagement, and future career success. Also key to this study was to measure the perceived value of formal debate v. other recognized active learning class activities.

Introduction

Those who have not personally engaged in formal debate may be surprised as to what the true ambitions of the process were originally designed to accomplish. A common misconception is that the goal of debate is to provide a given side of an argument that is stronger than the other. While it is true that both parties of a debate are offering arguments supporting their particular side, the desired outcome is not about winning but rather about facilitating greater information (Bergstrom, 2020). When properly employed in academia, debate has been connected to increasing student interest and engagement, learning, and future career success (Majid, et al., 2019; 2017; Rogers et al., 2017; Woods, 2020).

Several academic programs across curricula at the undergraduate level have been successfully employing debate as a staple in their classrooms for decades. Examples include Law, Philosophy, Accounting, English as a Second Language (ESL), Biology, Physics, Sociology, Religion, Law, Business Management, Human Resource Management, Economics, Nursing, Medicine, Physical Education, Communications, Education, and more recently, Internet Technology (Camp & Schnader, 2010; Fandos-Herrera et al., 2019; Iberri-Shea, 2017; Nurakhir et al., 2020; Snider & Schnurer, 2006; Woods, 2020).

Employing formal debate in curricula has also been demonstrated to significantly heighten a critical skill set known as soft skills, which has become increasingly more important by industry (iCIMS, 2017; Rabasca Roepe, 2017). Soft skills are defined as transferable skills regardless of the industry segment (MacDermott & Ortiz, 2017). Some soft skills most often mentioned in the research include critical thinking, teamwork, leadership, oral and written communication, decision making, and self-motivation (Kenton, 2021). This is important to note as the research shows that a gap currently exists between undergraduate students who rate their soft skills as proficient, while internship providers, as well as potential future employers, believe a significant number of students lack the appropriate level of soft skill mastery and as such, are ill-prepared for entering the workforce (Cohen, 2013; Merrell et al., 2017).

Of particular importance to this study is that while the research demonstrates multiple class activities have been engaged to heighten soft skill development within the sports management discipline, formal debate engagement is lacking. Within the relatively limited research available where sports management faculty have actively employed formal debate for their students, there is evidence suggesting its engagement and resulting heightened soft skill development as well as student interest, engagement, and learning (Dane-Staples, 2017, Shreffler, 2019; Tryce & Smith, 2015). This study sought to study from the vantage point of undergraduate sports management faculty their perception of the importance of enhancing student soft skills, what activities they found most effective towards this goal, and within these activities, their perception of the value(s) of engaging formal debate.

Review of the Literature

There is an abundance of research found in the literature regarding student career preparation that focuses on the increasing emphasis on soft skills by future employers (Dabke, 2015; Petrone, 2018; Majid et.al., 2019). A study by Jones et al., 2019, found that soft skills account for 85% of career success. Soft skills are defined as the more universal macro skillsets that include teamwork, leadership, written and oral communication, and critical thinking as opposed to the hard skills that are more specialized such as cost accounting skills for accountants.

Also found in the literature was a defined gap whereby students rate their soft skill mastery higher than do future employers. Several employers lament that students come unprepared for their initial foray into the workforce (Rabasca Roepe, 2017). These employers also suggest that the onus falls on the faculty to heighten student soft skill development. While many studies on the perceptions of both employers and students were available, interestingly, the group being charged with the responsibility of heightening student skills, the faculty, were not. The intention of this study was to thus remedy this omission by measuring faculty perception for specific areas of interest connected to this soft skill issue and which class activities when compared to debate, are perceived most effective in heightening student mastery. Debate has been demonstrated in the literature to be employed by multiple disciplines across curriculum who rated it as a highly effective activity in heightening soft skill development, student learning, interest/engagement, and future career success (Iberri-Shea, 2017; Rogers et al., 2017; Snider & Schnurer, 2016; Woods, 2020).

Methodology

The study sample was comprised of 108 (N = 108) North American-based undergraduate sports management faculty garnered from the North American Society for Sports Management listserv. The survey instrument was constructed through modifying five previous studies conducted by Chikeleze et al., 2018; Dane-Staples, 2019; Majid et al., 2019, Rogers et al., and 2017; Stewart et al., 2016. After testing for overall reliability and internal consistency, statistical analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses advanced in this study. For the testing, a combination of testing measures included ANOVA, with follow-up t-tests, Welsch testing, z-tests along with the reporting of means and standard deviation.

The testing addressed the perceived value of debate as a class activity between faculty who engaged in debate with their students and those who had not. Specifically, the perceived value was assessed in terms of debate’s efficiency in facilitating student learning, soft skill development, student interest and engagement, and preparation for future career success. The results as to the percentage of undergraduate sports management faculty said to engage their students in debate as a class activity, found that 62% (n = 65) were said to have engaged students in debate with the remaining 38% (n = 40) stated they had not.

The research question (RQ1), for the study asked; Is there a significant difference in the perceived value of incorporating formal debate in the curriculum between undergraduate sport management faculty who have previous experience engaging in the activity and those who have not?

Null Hypothesis Ho: There is no significant difference in the perceived value of incorporating formal debate in the curriculum between undergraduate sport management faculty who have previous experience engaging students in the activity and those who have not engaged.

Alternative Hypothesis Ha: There is a significant difference in the perceived value of incorporating formal debate in the curriculum between undergraduate sport management faculty who have previous experience engaging students in the debate activity and those who have not engaged.

Survey questions 28-32 were used to answer RQ1 based on results of a Likert scale with 1 = Not effective at all and 5 = Extremely effective.

Table 1 shows the rank order of the seven class activities perceived to be the most effective for impacting the combination of learning, soft skill development, interest and engagement, and future career success. Mean scores and standard deviations are reported for the two groups of faculty consisting of those who engaged students in debate, those that did not engage students in debate, and for the combined groups.

Table 1

Aggregate Mean Scores for all Categories Combined – Q28 – Q31

| Engaged | Not Engaged | Combined | ||||

| Class Activity | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Public Speaking | 4.14 | 0.73 | 3.96 | 0.84 | 4.05 | 0.78 |

| Major Individual | 3.03 | 0.96 | 3.10 | 1.08 | 3.07 | 1.02 |

| Case Study | 3.82 | 0.78 | 3.80 | 0.94 | 3.81 | 0.86 |

| Debate | 3.80 | 0.82 | 3.44 | 1.14 | 3.62 | 0.98 |

| Team Research | 3.42 | 0.96 | 3.45 | 1.08 | 3.43 | 1.02 |

| Ind. Presentation | 4.00 | 0.76 | 3.89 | 0.82 | 3.95 | 0.79 |

| Interactive Game | 3.60 | 0.91 | 3.29 | 1.08 | 3.45 | 1.00 |

| Grand Mean: | 3.63 |

The testing measured the perceived effectiveness of seven categorical items consisting of regularly employed class activities that included; 1) public speaking, 2) major individual research paper, 3) case study, 4) debate, 5) team research project, 6) individual presentation, and 7) interactive game. All activities were measured between the two independent groups – faculty who engaged students in debate and those who did not, as well as their found combined scores in aggregate. In aggregate, the engaged and not engaged faculty perceived public speaking to be the most effective class activity (M = 4.14, SD = .73, M = 3.96, SD = .84) impacting learning, soft skill development, interest and engagement, and future career success. On the other side of the spectrum, it was found that in aggregate, the lowest ranked class activity impacting learning, soft skill development, interest and engagement, and future career success was major thesis/individual paper (M = 3.03, SD = .96, M = 3.10, SD = 1.1). The combined or grand mean for the impact of all seven class activities was 3.63 which is considered moderately effective based on the five-point Likert scale with 3 = Slightly effective and 4 = Effective. No other activity besides public speaking scored above > 4.00.

When testing the between-group scores for the combined seven activities found the mean for those faculty who engaged students in debate (M = 3.69, SD = .85) was higher than those who did not engage (M = 3.56, SD = 1.0). A Welch t-test, however, revealed that no statistically significant difference exists between the groups based on an alpha at .05 t = 1.35, p = 0.177 > .05.

When separated for testing, debate ranked fourth among the seven most effective class activities according to the mean scores of the two groups combined (M=3.62, SD=.98) and for the faculty who engaged students (M=3.80, SD =.82) Those faculty who did not engage their students in debate ranked the activity fifth among the seven listed (M=3.44, SD-1.14).

While the aggregate results for the four combined student success areas provided valuable information, the researcher found it equally important to extend the testing to discern between the group and overall faculty perceptions for each of the four defined sub-categories consisting of 1) student learning, student, 2) soft skill development, 3) student interest/engagement, and 4) future career success. Specifically, the rationale for this next set of testing allowed for the researcher to determine if one or more of the four sub-categories had a more significant difference in the overall aggregate score. The results for each in order of listing are found below in Tables 2 – 5.

Table 2

Q28_1–Q28_7 – Student Learning Class Activities

| Engaged | Not Engaged | |||

| Class Activity | M | SD | M | SD |

| Public Speaking | 4.17 | 0.67 | 4.05 | 0.68 |

| Major Individual | 3.23 | 0.90 | 3.31 | 0.80 |

| Case Study | 4.02 | 0.63 | 3.95 | 0.79 |

| Debate | 3.75 | 0.79 | 3.38 | 0.99 |

| Team Research | 3.62 | 0.92 | 3.68 | 0.89 |

| Ind. Presentation | 4.11 | 0.77 | 3.95 | 0.80 |

| Interactive Game | 3.58 | 0.79 | 3.27 | 1.02 |

| Grand Mean: | 3.72 |

Public Speaking was the top-ranked class activity perceived to impact success dimension one, student learning, as reported by both the group of faculty who engaged their students (M = 4.17, SD = .67) and those who did not (M-4.05, SD=.68) Major Thesis Individual Paper was the lowest ranked class activity perceived to impact student learning according to faculty who engaged students in debate (M=3.32, SD = .90) while interactive games (M=3.27, SD = 1.02) was rated lowest the group of faculty who did not engage students in debate. The grand mean score for all student learning activities was found at (M = 3.72), which was higher than the aggregate mean (M =3.63) but not significantly. Welch t-testing revealed an alpha of .05, t = -0.6514, p = 0.05157 > .05. Between-group testing revealed the mean score for the combined student learning activities for those who had engaged students in debate M = 3.78 was higher than M = 3.65 for those who did engage. When tested, no significance was found. Testing demonstrated with an alpha set at .05. t = 0.7785, p = 0.4387 > 0.05. The engaged group ranked debate activity as the fourth highest (M = 3.75) in terms of impacting student learning, whereas non-engagers ranked debate as the fifth highest (M = 3.38).

Next, Table 3 shows the rank order of the seven class activities perceived to be the most effective for impacting the second success dimension, soft skill development, as reported by faculty who engaged their students in debate (Engaged) and those who did not (Not Engaged).

Table 3

Soft Skill Development Class Activities – Q29_1 – Q29_7

| Class Activity | Engaged | Not Engaged | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Public Speaking | 4.46 | 0.59 | 4.08 | 0.89 |

| Major Individual | 3.16 | 1.00 | 3.10 | 1.13 |

| Case Study | 3.74 | 0.82 | 3.70 | 0.97 |

| Debate | 3.92 | 0.80 | 3.40 | 1.17 |

| Team Research | 3.78 | 0.88 | 3.68 | 1.10 |

| Ind. Presentation | 4.14 | 0.68 | 3.98 | 0.83 |

| Interactive Game | 3.52 | 0.90 | 3.05 | 1.18 |

| Grand Mean: | 3.69 |

Public Speaking was the highest-ranked activity for heightening soft skill development for both groups of faculty who engaged their students in debate (M=4.46, SD-.59) and for those who did not engage their students in debate (M=4.08, SD=.89). The lowest-ranked score for both groups was Major Thesis Individual Paper M = 3.16 M = 3.10). Debate, as a class activity to heighten soft skill development, was ranked third among faculty who engaged students in debate (M=3.72) and fifth among faculty who did not engage students in debate (M=3.40). The grand mean for all seven class activities heightening soft skill development was M = 3.69, which was higher than the mean score of the seven activities impacting the aggregate of student learning, soft skill development, engagement, and future success (M = 3.63). No significant difference was apparent for the grand mean based on an alpha at .05, t = -0.2986, p = 0.7657 > 0.05. Between groups, the mean difference between those who engaged students in debate (M-3.82) was higher than faculty who did not engage students in debate (M = 3.57). The Welch t-test revealed no significant difference based on an alpha at .05 t = 1.2821, p = 0.2036 > 0.05.

Next, Table 4 shows the rank order of the seven class activities perceived to be the most effective for impacting the third success area, student interest and engagement, as reported by faculty who engaged their students in debate (Engaged) and those who did not (Not Engaged).

Table 4

Q30_1 – Q_7 – Student Interest/Engagement Class Activities

| Class Activity | Engaged | Not Engaged | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Public Speaking | 3.43 | 0.97 | 3.45 | 0.88 |

| Major Individual | 2.44 | 1.04 | 2.85 | 1.14 |

| Case Study | 3.69 | 0.85 | 3.75 | 0.95 |

| Debate | 3.72 | 0.86 | 3.46 | 1.19 |

| Team Research | 3.14 | 1.01 | 3.23 | 1.17 |

| Ind. Presentation | 3.51 | 0.92 | 3.56 | 0.79 |

| Interactive Game | 3.91 | 1.03 | 3.71 | 1.11 |

| Grand Mean: | 3.42 |

In terms of impacting Student Interest/Engagement, the top-ranked class activity for faculty who had previously engaged students in debate was Interactive Game (M = 3.91, SD = 1.03). Case studies (M = 3.75, SD = .95) was ranked the highest among faculty who did not engage students in debate. The lowest ranked or least effective score for both groups was Major Thesis Individual Paper (M = 2.44, SD = 1.04, M = 2.85, SD = 1.14). The aggregate sum score for Student Interest/Engagement was M = 3.42 which, when tested against all four categories, indicated a means score of 3.63 which was significant at an alpha of .05, t = 2.34, p = -0.02043 < .05. Between-group scores were M = 3.46 for faculty who engaged students in debate and M = 3.38 for faculty who did not engage students in debate. No significant difference was found between the independent variables of those who engaged students in debate and those who did not, based on alpha at .05, t = -0.1006 0.329, p = 0.92 > 0.05. Therefore, the null hypothesis was accepted. Faculty who engaged students in debate reported a mean score of 3.72 (SD = .86) for debate impacting engagement/interest while faculty who did not engage students in debate reported a slightly lower mean score of 3.46 (SD = 1.2).

Finally, Table 5 shows the rank order of the seven class activities perceived to be the most effective for impacting the fourth dimension of success, future career success, as reported by faculty who engaged their students in debate (Engaged) and those who did not (Not Engaged).

Table 5

Q31_1 – Q31_7 – Student Future Career Success Activities

| Class Activity | Engaged | Not Engaged | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Public Speaking | 4.50 | 0.69 | 4.26 | 0.91 |

| Major Individual | 3.31 | 0.92 | 3.15 | 1.27 |

| Case Study | 3.84 | 0.82 | 3.79 | 1.03 |

| Debate | 3.81 | 0.83 | 3.51 | 1.21 |

| Team Research | 3.89 | 0.92 | 3.59 | 1.12 |

| Ind. Presentation | 4.25 | 0.67 | 4.08 | 0.87 |

| Interactive Game | 3.40 | 0.91 | 3.13 | 1.02 |

| Grand Mean: | 3.75 |

The highest-ranked activity contributing to Future Career Success (Q31) was public speaking for both faculty who engaged students in debate (M = 4.50) and for those who did not engage students in debate (M = 4.26). The lowest ranked score for both groups was Major Thesis Individual Paper (M = 3.31, M = 3.15). The total mean score or grand mean for future career success activities was M = 3.75, which, when tested, was found not to be significantly higher than the aggregate average at M = 3.63 with alpha .05, t = 0.873, p = 0.3839 > .05. The aggregate group mean score for faculty who engaged students in debate was (M = 3.80) while the group mean score for those who did not engage was (M = 3.44). The Welch t-test revealed no significant difference with alpha at .05, t = 1.03, p = 0.31. The grand mean score for the category of debate was 3.69 (M = 3.69) which ranked fifth out of seven categories for both those who engaged students in debate and those who did not (M = 3.81, M = 3.51).

For the next set of testing the focus was exclusively on the perception debate as class activity by both sample groups and in aggregate. Table 6 illustrates the combined mean aggregate scores for each sample group’s perception of the impact of debate as a class activity, on the combination of all four dimensions of success including student learning, soft skill development, student interest/engagement, and future career success.

Table 6

Debate Perception between Engaged Students in Debate Activity/Not Engaged

| Engaged | Not Engaged | |||

| Category | M | SD | M | SD |

| Student Learning | 3.75 | 0.79 | 3.38 | 1.0 |

| Soft Skill Development | 3.92 | 0.80 | 3.40 | 1.2 |

| Student Interest/Engagement | 3.72 | 0.86 | 3.46 | 1.2 |

| Career Success | 3.81 | 0.83 | 3.51 | 1.2 |

| 3.80 | 0.82 | 3.44 | 1.1 |

The mean scores combined average for perceived effectiveness of the debate as a class activity impacting the four categories combined was 3.67 (M = 3.67). Debate, as a class activity, was considered moderately effective as a holistic class activity based on the Likert scale parameters of 3 = Slightly Effective and 4 = Effective. When examining scores between groups, faculty who engaged students in debate reported significantly higher mean scores (M = 3.80) than those who did not (M =3.44). The result of the Welch t-testing of the combined four categories was significant based on an alpha value of .05, t = 3.45, p = 0.00065 p > .001. The testing revealed that, in aggregate, the mean of those who engaged students in debate was significantly higher (M = 3.80, SD = 0.82) than the mean of those who had not (M = 3.44, SD = 1.1). This finding indicates that faculty who engaged their students in debate perceived the value of the debate activity as significantly more effective than those who had not. As such, in aggregate, the null hypothesis would be rejected.

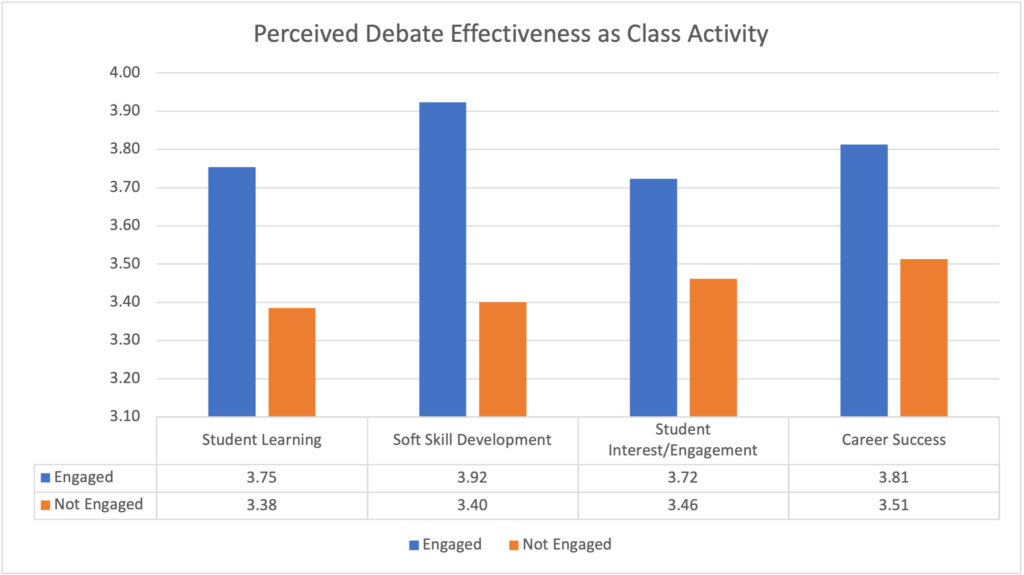

Figure 1 illustrates the variance in perceived effectiveness of the debate activity on each of the four outcome categories (Q28-Q31) among the faculty who engaged students in debate and those faculty who did not.

Figure 1

Perceived Effectiveness of Debate as Class Activity for Student Learning, Soft Skill Development Interest/Engagement, and Future Career Success

The results of the four Welch t-tests for the debate class activity effectiveness on the four dependent categories (Q28, Q29, Q30, Q31) found that only one (soft skill development Q29), was statistically significant. The results of the soft skill development testing, based on an alpha value of .05, t = 2.11, p = 0.04, indicated that the faculty who engaged students in debate as a class activity (M = 3.92, SD = .80) perceived it to be significantly more effective in soft skill development than those who did not engage students in debate (M = 3.40, SD = 1.2). As such, for this category, the null hypothesis was rejected.

There was no statistical difference found between those who engaged students in debate and those who had not in the categories of learning, interest/engagement, and future career success. In terms of the impact on learning, the mean scores for faculty who engaged their students in debate was 3.75 compared to 3.38 for faculty who did not engage students in debate. The results were not significant based on an alpha value of .05, t = 1.66, p = .102 > .05.

In terms of the impact on interest/engagement, the mean scores for faculty who engaged their students in debate were 3.72 compared to 3.46 for faculty who did not engage students in debate. The results were not significant based on an alpha value of .05, t = 1.19, p = 0.24 > .05.

The mean score for the impact of class activities on future career success was 3.81 for faculty who engaged students in debate and 3.51 for those who did not. The results were not significant based on an alpha value of .05, t = 1.36, p = 0.179 > .05. Based on the testing results, the null hypothesis was accepted, finding no significant difference in the perceived value of debate effectiveness for the categories of student learning, interest and engagement, and career success.

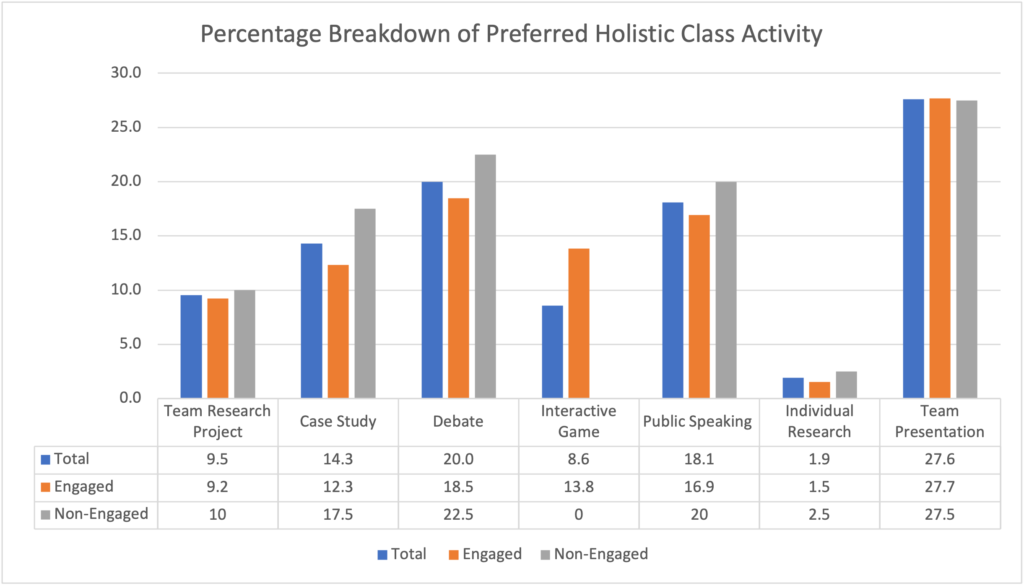

The final set of testing for RQ1, Q32, sought to find whether the undergraduate sports management faculty agreed to as was posed in the literature for multiple academic programs that debate is considered to be a highly effective class activity for enhancing multiple skills holistically. The testing focused on the perceived effect of heightening 1) learning, 2) soft skill development, 3) interest/engagement, and 4) future career preparation for students. For this area of testing, the undergraduate sports management faculty were asked “If limited to one class activity that would most effectively improve all four student success categories (learning, soft skill development, engagement/interest, and future success), which among the seven class activities would they select?” The results for the testing of faculty perceptions regarding the most holistically effective class activity are provided in Table 7. Note, activities related to debate are in bold print.

Table 7

Q32 Preferred Class Activity Holistically

| Total | Engaged | Not Engaged | ||||

| Class Activity | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Team Presentation | 29 | 27.6% | 18 | 27.7% | 11 | 27.5% |

| Debate | 21 | 20% | 12 | 18.5% | 9 | 22.5% |

| Public Speaking | 19 | 18.1% | 11 | 16.9% | 8 | 20% |

| Case Study | 15 | 14.3% | 8 | 12.3% | 7 | 17.5% |

| Team Research Project | 10 | 9.5% | 6 | 9.2% | 4 | 10% |

| Interactive Game | 9 | 8.6% | 9 | 13.8% | 0 | 0% |

| Individual Research | 2 | 1.9% | 1 | 1.5% | 1 | 2.5% |

Team presentation was the highest-rated class activity perceived as most effective holistically for both variable groups by those faculty who engaged students in debate and those who did not engage students in debate (27.7% n = 18) and those who do did not engage (27.5%, n = 11). Debate was found to be the second-highest ranked holistic class activity overall for both groups with those who engaged students in debate at (18.5% | n = 12), and those who did not engage students at (22.5% | n = 9). The lowest ranked class activity for all three groupings in aggregate was Individual Research Project (1.9% | n=2). The lowest-ranked activity for those who engaged students in debate was Individual Research Project (1.5%, | n=1). The lowest-ranked class activity for those who did not engage students was an Interactive Game with zero responses (0% | n=0). The percentage breakdown for each activity is further illustrated in Figure 4.8.

Figure 2

Percentage Breakdown of Preferred Holistic Class Activity

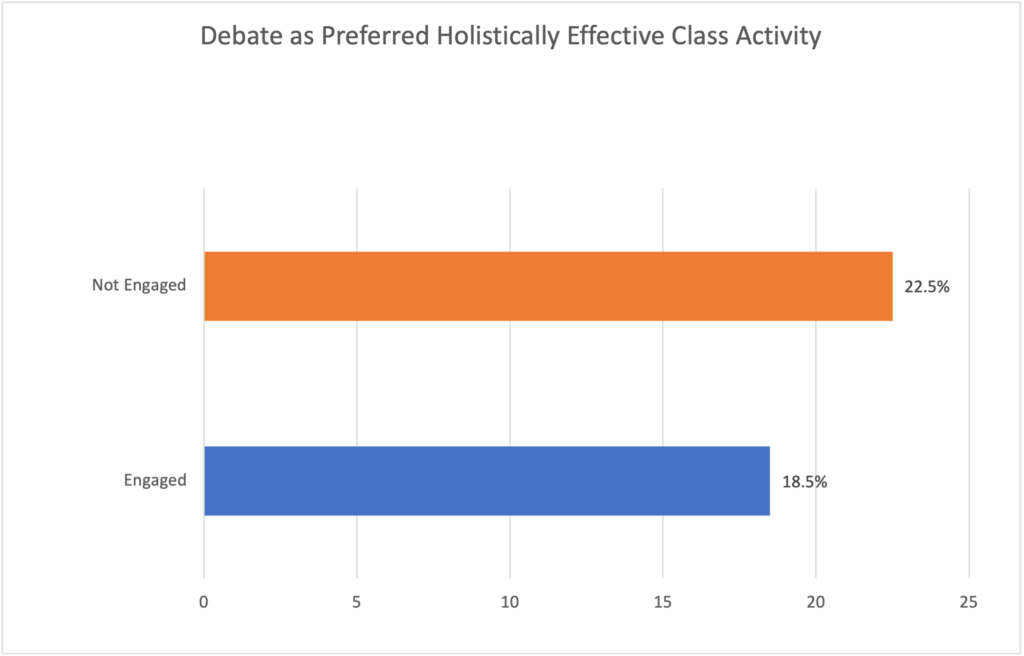

A follow-up z-test measured whether there was a significant difference between those who have previously engaged students in debate (n = 65) and those who have not (n = 40) regarding perceptions of the effectiveness of class activities holistically impacting student learning, soft skill development, interest/engagement, and future career success. The results of the z-test found no significance between the groupings based on an alpha set at .05, the value of z = .502, p = .617. Figure 4.9 illustrates the percentage difference between the two groups of faculty who engaged students in debate and those who did not.

Figure 3

Debate as Preferred Holistically Effective Class Activity

Based on this result, the null hypothesis would be accepted as no significantly perceived difference was found in the perceived effectiveness of debate as a holistic class activity between faculty who previously engaged students in debate and those who had not.

Additional analysis indicated those faculty who previously engaged in debate, 92% (n = 60), plan to continue the activity. When posed, it was found that 72% (n = 47) of the faculty who engaged students in debate reported they use the activity as a relatively minor assignment valued at less than < 10%, followed by 18% (n = 12) who valued the assignment at < 20% of the total grade. Of those who engaged students in debate it was found that just 3% (n = 2) of the 65 respondents who previously engaged students in debate claimed to teach debate as a standalone course. When asked whether debate should be considered as a standalone course in undergraduate sports management curriculum, the combined responses of faculty who did engage students in debate and those who had not, was M = 2.9 out of the 5-point Likert scale suggesting moderately low support.

Summary of the Results

The null hypothesis for Q1 was rejected due to a significant difference found via ANOVA and follow-up z-tests in the mean scores for Q28 – Q31, whereby those faculty who engaged students in debate were found to rate debate higher than those who did not when considering the impact of class activities on the categories of learning, soft skill development, interest/engagement, and future career success (p = < .001). When tested for statistical significance the testing revealed that, in aggregate, the mean of those faculty who engaged students in debate was significantly higher (M = 3.80, SD = 0.82) than the mean of those who had not (M = 3.44, SD = 1.1). The result of the Welch t-testing of the combined four categories was significant based on an alpha value of .05, t = 3.45, p = 0.00065 p > .001. As it was found that those faculty who did engage students in debate corresponded with a statistically significant higher mean score than those who had not, the null was rejected.

A follow-up forced-choice question, Q32, asked which of the seven potential class activities best served holistically in terms of heightening student learning, soft skills, interest/engagement, and future activity between undergraduate sport management faculty who did engage students and those engaged students in debate towards career success. The testing found both those faculty who had engaged students in debate and those who had not, selected debate as the second most effective activity of the seven. The results of the z-test found no significance between the groupings based on an alpha set at .05, the value of z = .502, p = .617. As there was not a significant difference between faculty who did engage students in debate and those who did not, the null was accepted.

Conclusions

In analyzing both sets of testing the null was rejected as the majority of the questions answered in terms of the overall value of debate, found that undergraduate sports management faculty who had engaged students in debate perceived its value at a statistically significantly higher level than those who did not. The testing for RQ1 analyzed the perceived value of debate from several vantage points. including 1) the overall perspective of debate as compared to six other class activities often utilized by faculty in heightening the areas of student learning, 2) soft skill development, 3) interest and engagement in debate, and 4) future career success. It also sought to assess whether debate is a more effective holistic tool for all four categories than the other activities as supported by previous research (Dane-Staples, 2019; Iberri-Shea, 2019; Rogers et al., 2017). The key focus of this research area was to add a new measure testing whether a difference existed in the perceived value of debate between undergraduate sport management faculty who have and who have not previously engaged students in debate. It is worth noting that the number of undergraduate sports management faculty responses supporting debate in the curriculum was surprisingly higher than what was expected by the researcher. The reason for this lower expectation of debate endorsement was based on the limited amount of discussion found in the literature directly related to the use of debate within sports management programming. The results found that overall undergraduate sports management faculty are both accepting of and engaged in debate with roughly 60% of participants in this study having engaged their students in debate. There was a high degree of advocacy for debate by those who have engaged. It was found that 94% of those faculty members who did engage planned to continue to use debate in the classroom.

The between-group results of the testing found that faculty who engaged students in debate rated it statistically significantly more effective than those who did not in heightening the combined four individual areas of student learning, soft skill development, interest/engagement, and future career success. The results revealed that the combined four categories were statistically significant based on an alpha value of .05, t = 3.45, p = 0.00065 p > .001. The testing revealed that, in aggregate, the mean of those who engaged students in debate was significantly higher (M = 3.80) than the mean of those who had not (M = 3.44).

Further testing, however, indicated that while the mean scores were higher for each individual area, only one of the four areas, soft skill development, was found to be statistically significant between the two faculty groupings. This outcome demonstrates that the variance between groups for soft skill development was great enough to affect the aggregate score for the four combined categories. This strong connection to soft skill development by the faculty who engaged their students in debate also supported what was found by researchers from multiple academic disciplines in that the activity is regarded as a highly effective tool for student soft skill development (Chikeleze et al., 2018; Merrell et al., 2017; Nurakhir, et al., 2020).

The final analysis for RQ1 sought to determine whether debate was perceived as a highly valuable holistic activity that can offer multiple opportunities towards heightening student success in the four areas of 1) learning, 2) interest/engagement, 3) soft skill development, and 4) preparation for future career success. Faculty were instructed to choose only one of the seven activities they perceived as best suited. Results indicated debate ranked second of seven potential learning activities for both samples including those faculty who did engage students in the debate process and those who did not. This finding also connected to the overall consensus of multiple academic programs found in the literature whereby debate was cited as a highly effective multi-functional activity that simultaneously heightens important student skillsets (Figueira et al., 2019; Iberri-Shea, 2017; Rogers, et al., 2017; Snider& Schnurer, 2006).

As noted, both the faculty group who engaged students in debate and those who did not each ranked debate at the same relatively high-level level among seven choices, specifically fourth in terms of individual value and second in terms of holistic value. The results suggest that faculty who do not engage their students in debate understand its value through their colleagues who do engage students in the learning activity. This study also provides that the value of debate is endorsed by both those who have engaged students and those who have not. This equal ranking of debate by both groups did not however correlate statistically to an equal endorsement.

It was discerned from the testing that 94% of those faculty who engaged in debate plan to continue. This finding is important as it suggests that once engaged in debate its perceived value increases. It was also found that a relatively small percentage at under 4%, there were also faculty that did not desire to continue using debate. The majority of the reasons offered as to why they chose not to continue were that they preferred other activities, or they were now teaching courses that did not lend themselves to the activity.

It was demonstrated that while debate has been a successful activity in the classroom, there is hesitancy by undergraduate sport management faculty to expand its usage. Of the 106 participants who responded, 25% (n = 28) agreed or strongly agreed that debate should be considered as a standalone course in undergraduate sports management curriculum compared to 36% (n =38) who disagreed or strongly disagreed. The remaining 38% (n = 40) neither agreed nor disagreed suggesting a less than enthusiastic endorsement of debate as a standalone course.

When asked of both those who had engaged students and those who did not as to what were the main concerns of employing debate, several participants reported they either experienced or were fearful of issues students spending more time quarreling than listening, were incapable of engaging in the process, and were uncomfortable engaging in potentially controversial subject matter. These findings align with the literature as to the potential pitfalls experienced by faculty that engage in debate as a class activity (De Conti, 2013; Felton, 2009; Tannen, 1999).

In gauging the results as to the effectiveness of debate on dimensions of success, it can be seen as a double-edged sword. While debate can potentially provide improvement in multiple student areas, when improperly employed, the negative outcomes may supersede its usefulness. It also provides an interesting dilemma as to assess whether undergraduate sports management faculty would be willing to do the additional work to ensure a successful outcome when they can rely on other activities that while potentially not as holistically valuable, pose no potential threat. This finding also suggests that the potential remedy to mitigate these fears relies on debate practitioners within the sports management discipline. It is posed that if those undergraduate sports management faculty who effectively engage in debate in their classes escalate their reporting of successful interactions in industry journals, conferences, workshops, and curriculum meetings, their colleagues may in turn be more open to incorporating the activity in their own courses.

Future Considerations

It is hopeful that the results of this study will lead to continued research in this area that includes faculty discussion and the potential adoption of new activities to strengthen the learning, interest/engagement of students. These additional class activities may similarly allow for increasing student preparation for future career success.

It was demonstrated that while debate has been a successful activity in the classroom, there is hesitancy by the majority of the undergraduate sport management faculty to fully utilize the activity. The majority of the faculty reported that debate was employed as a relatively minor activity toward a student’s total grade. It was thus proposed that this marginalized approach may be an area of future research that could allow for a deeper understanding of how to avoid these potential negative outcomes and that if this was accepted, a more robust usage of debate would be employed that would result in a higher level of student engagement, learning, soft skill development, and future career success.

Based on the results garnered from the fear of using debate in the classroom, it would be useful to measure whether those not inclined to engage in debate would consider implementation if an outside expert monitored the process. This suggestion serves as an interesting area for a future immersive, qualitative study. This extended research may also help to explain the results found in the study herein where faculty who chose not to engage in debate still rated it as a highly effective, holistic activity for heightening student learning, soft skill development, interest/engagement, and future career success. Along these lines of testing, one might also seek to correlate whether a test group consisting of students who were engaged in debate prior to engaging in a different graded activity i.e., case study, team presentation, etc., found greater success than students in the control group who were not exposed to debate.

A connected area of future study would be to utilize the same testing method applied to a resulting case study or business plan competition. One could measure whether the test group of competitors who had been engaged in the debate process one month prior to the competition performed at a higher level than the control group who were not offered the opportunity. Regardless of the modality of research (qualitative or quantitative), the target population (students, faculty, and employers), and the specific focus in the realm of debate in the sport management discipline, future studies are recommended to strengthen and enhance the potential for embedding debate in academic classes.

References

- Camp, J. M., & Schnader, A. L. (2010). Using debate to enhance critical thinking in the accounting classroom: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and U.S. tax policy. Issues in Accounting Education, 25(4), 655-675. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace.2010.25.4.655

- Chikeleze, M., Johnson, I., & Gibson, T. (2018). Let’s argue: Using debate to teach critical thinking and communication skills to future leaders. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(2), 123-137. https://doi.org/10.12806/v17/i2/a4

- Cohen, D. (2013, March 20). Learning to lose to learn — a funny thing about arguments: Dan Cohen at TEDxColbyCollege. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5-QZugvy0g

- Dabke, D. (2015). Soft skills as a predictor of perceived internship effectiveness and permanent placement opportunity. IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 9(4), 26-42.

- Dane-Staples, E. (2019). Assessing a two-pronged approach to active learning in sports sociology classrooms. 13(1), 11-22. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2018-0019

- De Conti, M. (2013). Debate as an educational tool: Is polarization a debate side effect. In G. Kišiček & I. Ž. Žagar (Eds.), What do we know about the world? Rhetorical and argumentative perspectives (pp. 275-300). Pedagoški inštitut/Educational Research Institute.

- Edwards, R. (2008). Competitive debate. Alpha.

- Fandos-Herrera, C., Jiménez-Martínez, J., Orús, C., & Pina, J. M. (2019). Introducing the discussant role to stimulate debate in the classroom: Effects on interactivity, learning outcomes, satisfaction and attitudes. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 380-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1366437

- Felton, M., Garcia-Mila, M., & Gilabert, S. (2009). Deliberation versus dispute: The impact of argumentative discourse goals on learning and reasoning in the science classroom. Informal Logic, 29(4), 417-446. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v29i4.2907

- Iberri-Shea, G. (2017). Many more sides: Debate across the curriculum and around the globe. Contemporary Argumentation & Debate, 37, 75-88.

- iCIMS.com. (2017). New research defines the soft skills that matter most to employers. https://www.icims.com/company/newsroom/new-research-defines-the-soft-skills-that-matter-most-to-employers/

- Kenton, W. (2021, February 25). Soft skills. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/soft-skills.asp

- MacDermott, C., & Ortiz, L. (2017). Beyond the business communication course: A historical perspective of the where, why, and how of soft skills development and job readiness for business graduates. IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 11(2), 7-24.

- Majid, S., Eapen, C. M., Aung, E. M., & Oo, K. T. (2019). The importance of soft skills for employability and career development: Students and employers’ perspectives. IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 13(4), 7-39.

- Merrell, B., Calderwood, K. J., & Graham, T. (2017). Debate across the disciplines: Structured classroom debates in interdisciplinary curricula. Contemporary Argumentation & Debate, 37, 57-74.

- Nurakhir, A., Nindya Palupi, F., Langeveld, C., & Nurmalia, D. (2020). Students’ views of classroom debates as a strategy to enhance critical thinking and oral communication skills [Classroom debates; critical thinking; nurse education; oral communication skill; students’ views]. 2020, 10(2), 130-145. https://doi.org/10.14710/nmjn.v10i2.29864

- Rabasca Roepe, L. (2017, August 18). Why soft skills will help you get the job and the promotion. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lisaroepe/2017/08/18/why-soft-skills-will-help-you-get-the-job-and-then-promoted/?sh=3b87d77154b8

- Rao, P. (2010). Debates as a pedagogical learning technique: Empirical research with business students. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal, 4(4), 234-250. https://doi.org/10.1108/17504971011087531

- Rogers, J. E., Freeman, N. P., & Rennels, A. R. (2017). Where are they now(?): Two decades of longitudinal outcome assessment data linking positive student, graduate student, career and life trajectory decisions to participation in intercollegiate competitive debate. National Forensic Journal, 35(1), 10-28.

- Shreffler, M. B. (2020). Controversial topics in the classroom: Debates on ethical issues in sports. Management Education Journal, 14(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2019-0022

- Snider, A., & Schnurer, M. (2006). Many sides: debate across the curriculum. International Debate Education Association.

- Stewart, C., Wall, A., & Marciniec, S. (2016). Mixed signals: Do college graduates have the soft skills that employers want? Competition Forum, 14(2), 276-281.

- Tannen, D. (1999). The argument culture. London: Virago.

- Tryce, S. A., & Smith, B. (2015). A mock debate on the Washington Redskins brand: Fostering critical thinking and cultural sensitivity among sports business students.sports Management Education Journal, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2013-0016

- Woods, D. M. (2020). Teaching tip: Active learning using debates in an IT strategy course. Journal of Information Systems Education, 31(1), 40-50.